In celebration of #ChecklistDay, here’s my checklist from this weekend:

In celebration of #ChecklistDay, here’s my checklist from this weekend:

One day last week, the sun, as it sometimes does, woke me up. It poured in through the dormer window that illuminates my small, fourth floor room in a building more than five times as old as I.

A view across my room, from my bed.

Maybe I should have thrown a pillow over my face and turned back over to go back to sleep, and some days I would have later regretted that I didn’t, but I got up. It’s an unusual trait for a college student, but I revel in the mornings. The promise of a fresh day always seems laden with hints of magic. The stirrings of life beckon me to my walk across campus. I don’t always make the walk across campus to Erdman—many mornings I merely eat microwaved oatmeal with dried fruit and nuts—but I never regret it when I do. The quiet of campus when few other students are crossing the greens and ducking through senior row is a treasure, a time for me to reflect and think. As if that weren’t reason enough, in and of itself, breakfast often offers one the chance to eat with one of my best friends, Rachel.

A photo from a garden next to New Dorm Dining Hall, showing one of my favorite spots to spend time after eating.

Food has, over my time at Bryn Mawr, become a ritual of friendship. Shared meals in the dining hall, lingering a bit longer than we should are a treasure—everyone needs to eat eventually, so eating together is an easy way to meet. I grew up in a family where we ate together, and as I went off to college I suppose I continued to do so, in a way. I eat supper nearly every night with people who are linked to me through traditions, part of my traditions family, I eat breakfast with a friend from my first-year hall, I eat lunch with friends from my first year, geology field trips, and friends with whom I have similar bonds.

Some days I don’t eat with friends and instead I read, but either way, the time I spend eating is a way of cementing my sense of place here.

On Monday, we were supposed to have a field trip to Beltsville, PA. The site is an outcrop of Devonian shale and siltstone–fine grained, mud-derived rocks that formed more than 350 million years ago. Eager for my field day, I got up at 6:30, dressing in cargo shorts, a sturdy button-down, emptying my backpack save for necessities for class, sliding my holstered swiss army knife onto a belt, and tying my hair back in a bandana. A few hours later, I grabbed out my raincoat and threw it on, shrugging my backpack on top. I set out for breakfast, walking through the rain on campus.

Unfortunately, our field trip was cancelled, a fact of which I was blissfully ignorant until I arrived in the paleontology lab, where we were to meet for our trip. While we were denied the field work that I was so looking forward to, we still had a wonderful time.

A few samples of fossiliferous rocks with a hand lens.

When I walked in, I noticed more than half a dozen trays, jammed full of fossiliferous shale. When we had all assembled, our professors, Pedro and Katherine Marenco, explained that the rainy conditions made the field site too hazardous. The trays were full of samples collected by students on previous trips to the same location. Our task? To fill up gallon bags of rock, two apiece, and catalogue the fossils in each rock.

A sample showing crinoid stalks and brachiopods.

We spent the next three hours and more identifying fossils, puzzling over cryptic patterns in rock, and trying to figure out whether the fossils were in the same shapes as the original organisms or inverted. Each rock held new samples–this one another fragment of a trilobite exoskeleton, another a new brachiopod (a shelled organism). The different organisms told us the environment must have been marine, a shallow sea. Reef-builders, such as earlier corals and bryozoans (a coral-like organism) plentiful in the Devonian. Some fossils were deformed, stretched out of shape, showing us that the rocks had been subjected to considerable strain after they formed. Many fossils were broken, not from the deformation or from rocks breaking, but from the original environment’s energy.

A well-preserved external mold of a brachiopod.

A fragment of a trilobite.

From the rocks we could build pictures of the oceans that must have existed near the shores of what would become North America. Flower-like crinoids would have sprouted from the floor, which would have been sprinkled with corals and bryozoans (coral-like organisms). Brachiopods and some bivalves (both shelled organisms) would have lain on the floor while trilobites swam and crawled around. With just a little thought, work, and a microscope, we can see so much. Here, in the rocks, we can see just a fragment of the mysteries that scientists are still working to unravel.

To quote Rachel Carson, as she wrote, in The Edge of the Sea, “to stand at the edge of the sea… is to have knowledge of things that are nearly as eternal as any earthly life can be.” So it is with these rocks, these traces of ancient life, some foreign to our eyes, some barely different in appearance than some of our modern organisms.

My name is Amelia McCarthy; I’m a geology and math double major at Bryn Mawr and I have a love for field work and ecology. I also love to read, play music, learn new words, dance, and draw, when I’m not busy in lab, doing homework, or distracted by trying to figure out what kind of organism or creature I just found.

This summer, I went to SEA, or Sea Educational Association, for a study abroad program. I spent my summer doing academic work, sailing a tall ship (the beautiful Robert C. Seamans), and conquering my fear of jumping off the bowsprit.

The Seamans at anchor off Orona, Phoenix Islands, Kiribati. Photo by Claire Bradham

The summer started in Cape Cod, with twenty-five students of college age sharing two cottages, three or two to a room. We cooked each other meals and went to class together. We went grocery shopping together and negotiated each day’s food plan. We spent time after our classes, which took up just shy of six hours a day, studying, playing games, reading for our classes and pursuing research topics that we picked. While the shore component was wonderful, it was eclipsed by the second part of the summer, for which we were preparing.

A beach in the Pago Pago area. Photo by Claire Bradham

After three weeks in Cape Cod, counted in solid understandings of topics we’d barely heard of before, finished research proposals, trips to the beach, sweaters at night, and a growing camaraderie, we left for our week-long break, to regroup in Pago Pago, American Samoa. There we would join our ship, the Robert C. Seamans, our home for the next five weeks as we sailed north to within three degrees south of the equator, and meandered through the Phoenix Islands.

Me, jumping into the waters just offshore of Orona. Photo by Claire Bradham

The Seamans underway with the mains’l, main stays’l, fore stays’l, and jib set. Photo by Cassidy Manzonelli

SEA has a two part mission: involve undergraduates in and enchant them with meaningful research, and preserve a heritage of sailing. This summer, they offered a trip to the Phoenix Islands, a remote chain of atolls in the equatorial and sub-equatorial South Pacific. The Phoenix Islands are part of an incredible protected area, PIPA, set up and overseen by the government of Kiribati, which is, itself, a small island nation in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Along with my scientific research–which examined the connection between diversification of plankton, organisms that cannot swim against the current, and the proximity of islands–I was responsible for a research paper on policy and its effects, focused on the area, with a field research component. I was also responsible for helping with the ship’s work during normal operation, and during one of our stops. Once a week, the entire ship gets cleaned as much as possible in three hours, and every morning one watch is responsible for a less extensive cleaning. There was plenty of work to be done, though there were times, such as dawn watch (1-7 a.m.) where you might find yourself with some spare time. Then, whoever was not busy might be sent to work on their academics.

Each day on the ship, I stood at least six hours of watch. One watch, six hours, is followed by twelve hours off: hours for sleep, eating, studying, relaxation, and sometimes more ship’s work and class. Everyday, save Sunday, class was held in the afternoon, with all of us crowded onto the quarterdeck. Some days we focused on oceanography, some on natural history, and some on the history. Class was an update on the ship’s scientific mission, a time to see the rest of the crew, and a time to learn more skills and information.

While class may have been called class, on the ship, most of the learning took place outside of class. If you were on watch, you were practicing or learning skills, whether in lab, doing and processing deployments (plankton nets and water sampling devices), or on deck, looking after the ship and sailing. If you were off watch, you might be relaxing, but chances were good that if you weren’t asleep, you were still learning. You might be working on your research project, or asking how to tie a knot, or learning how to clean the head (bathroom) faster.

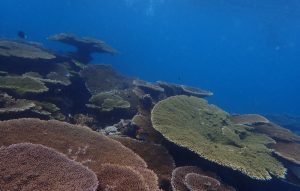

Leading up to the trip, one of the most frequent questions people asked when they heard about what I was going to be doing was “do you get seasick?” The answer is yes. That being said, seasickness was a small price to pay for the trip. I got to glimpse some of the most pristine reefs on earth, meet incredible people, do science that matters, and sail.

A picture that does no justice to the area–Kanton atoll, Phoenix Islands. Photo by Claire Bradham

There is something indescribably beautiful about the open ocean, out of sight of land and, more often than not, far from any other ships. When squalls drenched our decks and dimmed the skies, it was no less awe-inspiring than clear nights when the milky way stood out starkly above the darkened waters or clear days when the ocean was the most brilliant hue of blue. Close to the islands, there was the interruption of the horizon, but we were rewarded for our sacrifice of the grandeur of the open ocean: glimpses of sharks and fish, a plethora of birds, and, when time and weather permitted, snorkeling and exploring the islands were a few of the benefits.

For me, it was an especially rewarding experience. The intensity and limited showers certainly aren’t for everyone, and conditions can get uncomfortable, but I want to do field research in ecology someday, probably in the oceans, and such an immersive environment, so close to what I want to do, was magical.

It wasn’t just the science, the academics, the ocean, or the sheer beauty; it was more than even the combination of those which made the trip so incredible. It was the norms, routines, companionship, and atmosphere that both the experience and the way it was structured fostered. When they were off watch, the paid crew could often be found playing music, staring out at the ocean while conversing, or playing cards. A waiting list formed for certain books on board the ship–books read in our precious and, in truth, stolen, free time. We could laugh and talk freely on trivial subjects or about deeply held convictions. We learned each other’s personalities, quirks, and favorite parts of the trip. In short, the trip left an indelible mark, and one that I carry with pride.

Returning to land was difficult–most of us had at least some culture shock on re-entry. For me, there were two things that made the return more bearable–a trip to visit where I grew up, in Illinois, and the knowledge that I would be returning to Bryn Mawr.

Even when I find Bryn Mawr difficult, I find here some of that same sense of companionship and beauty. Here the stars are harder to see at night, but on the right nights, they are speckled instead with lanterns.